Nolli’s Map offers a comprehensive representation of the city of Rome

embedded in the Agro Romano (the rural area of plains and hills

surrounding the city within the current municipality of Rome). It

shows the city not just as an assemblage of buildings and monuments,

but more as an integrated whole, a system of built structures, street

networks, and the grand artery of the Tiber River, interwoven with

designed and natural greenery set within the larger landscape. This is

illustrated by the equal attention and care given to the green spaces

as well as the built structures, uninhabited open areas as well as the

inhabited neighborhoods within the city walls and beyond. Rome, as a

mental construct, extended beyond the physical boundary of the city

wall.

Nolli expanded the representation of the city outside the Aurelian

Walls on the north and west sides, where significant villas were

constructed along the consular roads of Via Salaria, Via Flaminia, Via

Nomentana, and Via Aurelia from the sixteenth century onwards. In

contrast, on the south and east sides, the pastoral landscape of the

Roman Campagna reigned. Dotted with castle ruins and sparsely

inhabited by herdsmen and grazing cattle, this less prestigious

landscape was neatly cropped out of Nolli’s map just outside the

walls. Nonetheless the excluded landscape was also part of Rome. Its

more idyllic views have been immortalized by Claude Lorrain and other

artists.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Adele L. Lehman, in memory of Arthur Lehman, 1965. (source)

Most maps of Rome published over the two centuries between Leonardo

Bufalini’s Map (1551) and Nolli’s Map (1748) extend the city beyond

the walls, attesting to the common perception of the city embedded in

the broader landscape. Among them, the Nolli Map is the first truly

scientific representation of the city, combining a detailed and

accurate survey with the now-standard Mercator orientation with north

at the top. Nolli’s Rome is represented as a green city, forming a

striking contrast with the earliest maps and views of the city. If we

define green spaces broadly as plots of land containing any kind of

vegetation – villas, gardens, parks, planted squares, tree-lined

avenues, kitchen gardens, orchards, olive groves, pastures,

cemeteries, and other uninhabited open spaces – the large ratio of the

green spaces to built space in Nolli’s Map is quite striking even at

first glance. In Nolli’s time, green spaces occupied approximately

two-thirds of the surface area within the Aurelian Walls, forming a

zone of greenery encircling the urban core. His Map represents the

culmination of three centuries of the development of various forms of

greenscapes in and around the city.

Of all the types of green spaces we have tentatively listed above

according to design and function, Nolli identifies six: villa,

giardino (garden), vigna (vineyard), orto (kitchen garden), canneto

(reed plot), and prati (fields). Of the labeled green spaces on

Nolli’s Map, the vigna has the largest number of occurrences (vigna 120, villa 77,

orto 33,

giardino 25,

prati 3, canneto 2

). These numbers do not include the plots that were left unlabeled,

such as numerous gardens in the city center, or the smaller plots of

the vigna, orto, or canneto.

The vigna in Rome

The vigna is a key term and concept for

understanding one of the quintessential aspects of Rome, namely its

propensity for strong connections with the land. From the time of the

Early Republican statesman Cincinnatus (ca. 519 – ca. 430 BC) through

the early modern era, cultivation of the land was perceived to be one

of the most noble forms of civic virtue. In the social history of

early modern Rome, ownership of a vigna in the vicinity of the city

center was a requirement for citizenship. The vigna can be loosely

interpreted as a vineyard, often accommodating vegetable plots and

orchards. The term can be interchangeable with villa; in some cases,

it is used to mean an aristocratic estate with designed gardens and

agricultural land. Etymologically derived from the Latin word vinea,

in the dictionary of the Accademia della Crusca, it is defined as a

vineyard, an agricultural plot where vine grapes are planted in rows.

Indeed, for the plots labeled vigna on his map, Nolli adopts the

conventional iconography for vineyards used in contemporary

cartographical documents, the regular rows of vine grapes

characterized by their curly tendrils, separated by dotted lines (as,

for example, on large sectors on the Aventine Hill). The vigna was not

just a term indicating the agrarian character of a plot. It appears

regularly in legal documents and was used generically as a unit in

real estate transactions referring to a plot of land. Probably such

properties, when they contained no substantial architecture, were

commonly used as vineyards.

For the

orto (or kitchen garden), Nolli uses

parallel sets of broken lines flanking a dotted line indicating the

furrows, or in some cases parallel broken lines (as, for example,

plots on the Circo Massimo—the ancient Circus Maximus where chariot

races took place). Often these plots were irrigated from a well or

spring within the property or nearby and were equipped with

outbuildings. At the site of the Circo Massimo, we see several plots

owned by different entities, among them the chapter house of the

nearby church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin.

The term

villa, in contrast, denoted an estate

for a second residence as distinguished from the city palace. In most

cases it is located in suburban areas or in the countryside reachable

within a day, thus within an orbit of 70 – 80 kilometers from the

city, but as we shall see, it could be located within the walls, in

the area outside of the built-up core. It referred to the entire

estate, comprising the building for lodging and dining, the casino

(small, elegant building annexed to an aristocratic villa), the

giardino (formal garden with planted beds often laid out in a

geometric or embroidery pattern), tree-lined allées, the informal

park, agricultural fields of the vigna and orto, and in some cases

also woods and hunting grounds.

The large estate of a villa, for example the Villa Ludovisi (no. 382), was formed by purchasing and piecing together multiple vigne. The villa was a Renaissance phenomenon consciously modeled on the aristocratic villa of Roman antiquity. The vigna had always existed in Rome, but as a cultural concept it enjoyed a revival through the early modern reverence for ancient Roman literature, from Virgil’s Georgics to the agricultural literature of Varro, Columella, and Palladius. The biblical connotations of the Lord’s Vineyard with the pope as its custodian also became a theme that continued to define the character of Rome. The vigne were noted as a characteristically Roman feature also by early modern travelers, such as Montaigne, Montesquieu, and Goethe. In a nostalgic essay of 1975 entitled “When Rome was a Vigna,” Manlio Barberito, former president of the “Gruppo dei Romanisti,” laments a fast-disappearing Rome of cultivated fields, the remnants of which are still detectable here and there in the rooftop and balcony greenery and the courtyard gardens that adorn the modern city.

Cultivation and Production: vigna and orto

The vineyards were primarily for the sustenance of their owners or

their tenants, thus key to the economy and society of medieval and

early modern Rome. A ubiquitous presence around the inhabited area in

Rome since medieval times, they were a crucial component of the early

modern Roman landscape until the Unification of Italy in 1870.

Primarily for growing grapevine, they often included other types of

agricultural plots – kitchen gardens, orchards, olive groves, and reed

plots. The plant growing in the reed plot, the marsh reed, was used

for various utilitarian purposes, such as weaving baskets for grape

harvest and for constructing supports for the vine. Ecclesiastical

institutions commonly owned vineyards. Located in the vicinity of

churches, monasteries, and convents, vineyards, vegetable plots and

orchards were tended by the monks and nuns. Flowers were grown for

decorating altars, and medicinal plants for pharmacopeial needs.

Alongside the Hospital of Santo Spirito, the Jesuits were affluent

landowners. In the city center, they operated their mother church, the

Gesù (no. 902), their educational

institution, the

Roman College (nos. 846, 847),

and a garden for spiritual meditation at

Sant’Andrea al Quirinale (no. 177, Giardini del Noviziato de’

Gesuiti). They also owned large vigna properties at the peripheries of the

built city, at Castro Pretorio (

Villa del Noviziato de’ Gesuiti;

Villa Olgiati ora del Noviziato de’ Gesuiti) and on the Aventine Hill (

Giardino della Casa Professa dei Gesuiti;

Vigna del Noviziato dei Gesuiti).

Curated Nature: villa and giardino

In the second half of the fifteenth century, the influence of

humanistic and antiquarian culture, alongside the practical concerns

of social prestige, led to the revival of the culture of villas and

gardens of antiquity. A distinctive garden of the fifteenth century is

the

Viridarium of San Marco (1465-1469). Commissioned by Pietro Barbo (Pope Paul II, 1464-1471), it was

created as part of an effort to transform the Palazzo San Marco (no.

903) into a grand papal residence. Originally located at the southeast

corner of the Palazzo, within the crenellated building of the

Palazzetto San Marco (no. 905), it was a hanging garden raised above

street level and enclosed by double-tiered porticoes on all four sides

of its square plan. Intersecting paths divided the garden into four

compartments planted with trees, with a well at the center. The

spatial arrangement was inherited from the cloister gardens of

medieval monasteries intended for strolling and meditation. The

original garden was demolished in 1910 to make room for the Vittorio

Emanuele Monument; the current garden of the Palazzo Venezia is its

reconstruction, displaced to the southwestern corner of the block.

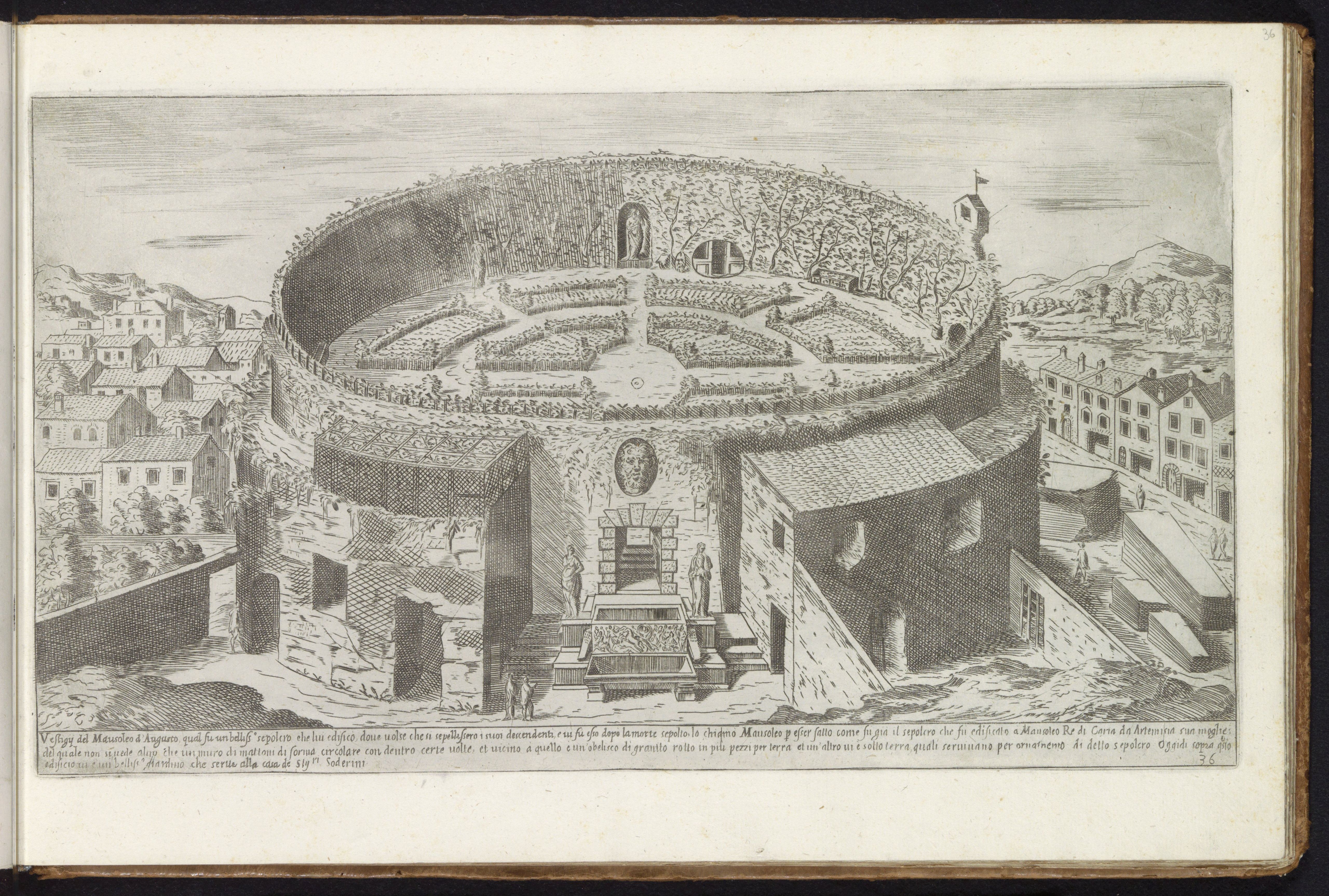

The sixteenth century saw a proliferation of villas and gardens both within urban and suburban districts. The Belvedere Sculpture Court (1484-1487) and the Della Valle Sculpture Court (1533) (no. 794) were courtyard gardens created for the display of ancient sculpture collections. The Villa Madama (1518, off the Nolli Map to the north) and the Belvedere Courtyard at the Vatican were terraced gardens developed on sloping terrain. Each terrace could be used for different purposes – different types of planting by terrace at the Villa Madama; planted beds, arenas for jousts or miniature naval battles at the Belvedere Courtyard (image: Perspective view of a jousting tournament in the Vatican; fireworks in the background. 1565, Etching and engraving. © The Trustees of the British Museum.). The Soderini Garden (no. 472) (image: Etienne Duperac, Mausoleum of Augustus, 1575, Engraving) within the Mausoleum of Augustus or the Horti Bellaiani, the garden of Cardinal Jean du Bellay, which in Nolli’s time became the orto of the Cistercians (Orto dei Monaci di S. Bernardo) in the exedra of the Baths of Diocletian made connections to antiquity by building directly on top of prestigious ancient sites.

From the second half of the century, large villas articulating different types of green spaces emerged. Villa Peretti Montalto (no. 199), the sole residence and villa for Felice Peretti (Pope Sixtus V, 1585-1590) and his family, was one of the most impressive in sixteenth-century Rome. Formed by a series of land acquisitions, it occupied a vast area extending from the present-day Piazza del Cinquecento in front of Termini Station to the Porta San Lorenzo; it was destroyed between 1860 and 1890 for the construction of the railway station. At the core of the property, the residential villa building, the Palazzetto Felice, was flanked by enclosed formal gardens with planting beds. Here, the urban form of the trident – three streets diverging from a single point – used in the urban design of Rome (e.g., Piazza del Popolo, no. 403, and the trident of the streets, Ripetta, Corso, and Babuino found at the top and center of Nolli’s map) – was applied within the garden. Compartments delineated by rows of trees accommodated ornamental plantings with a fountain. The walled complex of the Palazzetto Felice and the ornamental gardens were surrounded by vineyards (vigne), rendered with the characteristic iconography of curly tendrils, a wooded area indicated by trees, and kitchen gardens (orti) with parallel dotted lines. The Acqua Felice, the aqueduct completed by Sixtus V to serve the city, ran through the property, bringing water to the garden’s fountains, before reaching its terminus and display fountain, the Fontana dell’Acqua Felice (no. 205, also called Moses Fountain).

From the turn of the seventeenth century, a new type of villa emerged. Along the peripheries of the walled city were created large estates with vast stretches of wooded areas. The quintessential example, the Villa Borghese, is labeled “Villa Borghese detta Pinciana” and located at the top of the map, just right of center. The main villa building (1606-1621), designed by Flaminio Ponzio and Jan van Santen, faced a piazza on the façade side, and a fountain garden on the rear. It is flanked by formal gardens with parterres, one of which accommodates an aviary. Surrounding the formally designed core complex are numerous plots with trees, separated by paths arranged in geometrical layout. Here the emphasis of the villa had shifted from the formal gardens to the more informal planted areas where trees – even wooded areas – dominate. Villa Pamphilj is another vast estate that featured wooded areas. Nolli’s Map shows only a corner of it along its left-most edge.

In the eighteenth century, the construction of large villas along the consular roads outside the city walls continued. Most of these villas are outside the area represented on the Nolli Map. Here we will look at one that is included, the Villa Corsini in Trastevere (no. 158), an eighteenth-century renovation of the sixteenth-century villa of Cardinal Raffaele Riario. The garden is shown with square beds in the lower area and densely planted trees on the steep slopes of the Janiculum Hill, a zone that today hosts Rome’s botanical gardens. Cardinal Neri Maria Corsini had purchased the property in 1736 and commissioned elaborate fountains there, indulging the eighteenth-century taste for elaborate form and theatrical space. The garden is described in Giuseppe Vasi’s guidebook of Rome (1761). The Fountain of Tritons (1742), a quatrefoil basin with two tritons holding a fruit basket, was by Giuseppe Poddi (1704-1744), a sculptor who carved the rockwork of the Trevi Fountain. Further up the slope on the same axis is the Fountain of the Eleven Jets by Ferdinando Fuga (1699-1782). The fountains were fed by the Acqua Paola. The Belvedere del Gianicolo above was Vasi’s viewpoint for his Prospetto dell’Alma Città di Roma (1765) (Image: Giuseppe Vasi, Prospetto dell’Alma Città di Roma, 1765. Etching and engraving. British Library. ), which places the Villa Corsini at the center foreground of the panorama. Nolli uses the hatching technique for the contours of hills and elevated terrain; here he captures the changing topography by superimposing hatching on the areas planted with trees and vine, rendering in darker tones the part of the garden on the steepest slopes.

Urban Trees

Commonly assumed to be a product of

nineteenth-century urban planning in Rome as in Paris, the tree-lined

street goes back to at least the early seventeenth century. In Rome,

its appearance coincides with the period in which large villas with

vast expanses of wooded areas emerged in the suburbs. In 1611 Paul V

(pontificate 1605-1621) completed the first tree-lined street in

Trastevere,

Via di San Francesco a Ripa. The new

street directly connected the Porta Portese to the heart of the

Trastevere neighborhood. Initially planned to extend to Santa Maria in

Trastevere, it was only realized as far as San Callisto. The street

was not well maintained; Nolli shows no trees along it, most likely

because they had died or been removed by his time. But he recorded

numerous other instances of urban tree-planting from the seventeenth

and eighteenth centuries.

Alexander VII (pontificate

1655-1667) initiated a systematic project of tree-planting in piazzas

fronting basilicas and along routes leading to major pilgrimage

destinations, both within and beyond the Aurelian Walls. The project

targeted the south and east neighborhoods, which were sparsely

populated and largely undeveloped, thus lacking buildings or treed

estates that could provide shade to pedestrians or travelers on

horseback.

The first such scheme to be realized was the

quadruple rows of elms in the

Campo Vaccino (“cow pasture,” no. 927)

in 1656. The Roman Forum would not be definitively identified as such

until the nineteenth century. Called Campo Vaccino at this time, it

was a pasture and a cattle market picturesquely situated among

half-buried ruins. Extending from the Arch of Titus to the Arch of

Septimius Severus, the four rows of elms provided a shaded pilgrimage

route for the seven churches fronting the Forum. It created a wider

center lane for carriages and narrower side lanes for the pedestrians.

Several other planting schemes recorded on Nolli’s Map can be dated to

the pontificate of Alexander VII: the route around the

Aventine from the Marmorata to

Porta San Paolo; the

street heading southeast from the

Circo Massimo towards the convent of San Sisto; and the

river port of the Ripa Grande at

Porta Portese. At least two piazzas were planted. As the terminus of

the Via Sistina, the piazza on the apse side of Santa Maria Maggiore

(currently Piazza dell’Esquilino), marked by an obelisk (no. 50), was

planted with elm trees on either side

to form stage wings of a sort to frame the church.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. David Keppel, 1960.)

Piranesi’s view about eighty years later shows that the trees were not so well maintained. The Piazza di San Cosimato, the triangular piazza in Trastevere adjacent to the church now called San Cosimato (no. 1136), is a rare example of a planted piazza that survived the vicissitudes of modernization. Around 1743, Benedict XIV (pontificate 1740-1758) planted multiple rows of elms just inside the Aurelian Walls east of Porta San Giovanni, forming a promenade between the churches of San Giovanni in Laterano (no. 5) and Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (no. 21). Nolli’s map, published only five years later, records a grand-scale planting of five rows on one side and a single row on the other.

In-Between Spaces: canneto and prati

There were other green spaces apart from the more obvious categories

described above.

The canneto (reed plot) is a term attested since the fourteenth

century. It is normally found within a villa or a vigna. On Nolli’s

Map, canneti are shown with their recognizable iconography, tall

vertical stalks and long leaves branching out exuberantly to either

side. Only two such plots are labeled:

Canneto Magnani and Canneto Ghetti, just outside the Porta Maggiore. These appear to be independent

plots. Other identifiable canneti located within relatively large

villa or vigna estates bear the iconography of smaller marsh reeds. We

find the less dense version of canneti all over the city, but

especially in the vicinity of water: at the Villa Peretti Montalto to

the right side of the aqueduct Acqua Felice; on the Aventine, near

Porta San Paolo, and in the vigna of the clerics of Santa Maria in

Campitelli between San Giovanni in Laterano and Santa Croce. Some

plots within villas and vigne were left untended, and the reeds may

have grown there naturally.

The term prati on Nolli’s Map is used to refer to a large untended

space without a designated function, except pasturage. The stippling

used for these areas indicates undeveloped land without any fixed use.

It could be a public space or private property. The

Prati Pamphilj was the property of

the Pamphilj family, while the

“Prati de Can.ci Reg. di S. Ant.o Ab.e” (Field of the Canons of the

church of Saint Anthony Abbot), north of the Porta Salaria, belonged to an ecclesiastical

institution. The

“Prati del Popolo Romano”(no. 1069) (Field of the People of

Rome), between Porta San Paolo and Testaccio, was public property, managed

by the city. In Nolli’s time, it became the Non-Catholic Cemetery. We

will examine cemeteries in more detail in the next section. In most

cases they included some form of vegetation, whether planted or

naturally growing, thus they can be considered as green spaces.

Final Resting Place

In early modern Rome, cemeteries for Catholics were annexed to

churches and hospitals, located adjacent to or underneath them. Given

the large expanse of the uninhabited areas, inhumation within the city

walls did not seem to have posed a problem.

The

Cemetery of the Hospital of Santo Spirito

on the right bank of the Tiber was one of the largest Catholic

cemeteries in Rome. (no. 1235: Cappella del Santissimo Crocifisso nel

Cemeterio di Santo Spirito). Benedict XIV unsuccessfully tried to

relocate it to the Janiculum; he then commissioned Ferdinando Fuga to

reorganize the expansion in 1744. Other noted cemeteries are mostly

burial places for marginal people. A

mass grave for executed persons (no.

1051, Sepoltura de’ Giustiziati) was in the cloister of the church of

San Giovanni Battista Decollato in the Velabro. Those rejected from

the Christian community, such as suicides, bandits, vagrants, and

prostitutes, were buried at the

Muro Torto (no. 402, Sepoltura degli Impenitenti), outside the Aurelian Walls.

The Jewish Cemetery was originally located in Trastevere just outside

the current Porta Portese. It goes back to the fourteenth century,

when a statute of 1363 prohibited the burial of Jews within the city

but granted them a communal burial ground in Trastevere purchased for

that purpose. The location is shown on Nolli’s Map labeled

“Ortaccio degli Ebrei.” The term

ortaccio is derived from orto, combined with the pejorative suffix,

“-accio,” probably reflecting no deficiencies of the property itself,

but simply the anti-Semitism of the age. The Jewish Cemetery relocated

to the vicinity of the Circo Massimo area under Urban VIII

(pontificate 1623-1644), as the new Janiculum Walls constructed by the

Barberini pope interfered with the centuries-old burial ground. At

this point, the plots not built over and remained in the possession of

the Jewish community started being rented out as kitchen gardens.

The relocated Jewish Cemetery occupied the lower Aventine

overlooking the Circo Massimo, at the plots labeled

“Ortaccio Vecchio degli Ebrei” and “Ortaccio degli Ebrei.”

In 1775, a third adjacent property, the “Vigna Carridoro,” was

purchased to expand the cemetery. In consequence, half of the Circo

Massimo, on the Aventine side of the Marrana brook, was occupied by

the Jewish Cemetery until 1834, when it was forced to relocate again,

this time to the Comune di Roma’s Verano Cemetery. The former Jewish

cemetery on the Aventine has been converted into Rome’s Rose Garden,

with paths laid out

in the form of the menorah.

The Non-Catholic cemetery is the only early modern cemetery in Rome that has survived in its original location. Adjacent to Monte Testaccio, it is labeled “Prati del Popolo Romano” (no. 1069, “Luogo ove si seppelliscono i Protestanti”). Throughout the early modern period, the Testaccio area was unbuilt public property, used for pasturage, military drilling, and recreational outings. From the second half of the seventeenth century, the city started renting out grottoes carved into the Testaccio hill as wine cellars and leasing parcels of land for planting mulberry trees. Following the loose concession in 1671 by the Catholic authority granting decent burials to non-Catholics, the site appears to have been chosen as a burial ground by the Protestants for its remote location, absence of a controlling parish, public ownership, and tranquil and idyllic character. The nearby Pyramid of Gaius Cestius may also have lent a majestic funerary tone to the place.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 37.17.7. Gift of Edward W. Root, Elihu Root Jr. and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant III, 1937.

The earliest known burial is dated to 1716. The first mulberry trees were planted in 1671. Nolli shows almost the entire area planted with trees. Today it is shaded with cypresses and umbrella pines.

After Nolli

The modern city of Rome has much less green space than Nolli’s Rome.

From 1748 to 1870, not much changed in the urban fabric, including its

green fabric. When the Italian Troops reached Rome in September 1870,

they found a rather unimpressive city with only a third or less of the

total of 1470 hectares within the Aurelian Walls consisting of built

space. The built fabric was concentrated in the area delimited by the

Piazza del Popolo, the Campidoglio, and the bend of the Tiber

enclosing the Campo Marzio, largely corresponding to what the Nolli

Map shows as built space. The rest was a mix of villas, gardens,

vineyards, kitchen gardens, orchards, pastures, the occasional

canneto, and uninhabited land dotted with ancient ruins overgrown with

vegetation, where herdsmen brought their flocks to graze. The urban

infrastructure and way of life had changed little since the

seventeenth century.

The drastic change that altered

the cityscape almost beyond recognition – and which created, in a

couple of decades, most of the city we see today – came with the

unification of Italy. Soon after 1870, the state took control of urban

planning. The dismantling of religious institutions, the confiscation

of their land properties, the fragmentation of large aristocratic

estates – demolition and destruction progressed at an accelerated

pace. New government buildings and apartment blocks sprang up, and

streets and transportation facilities were constructed, mostly in open

zones previously occupied by orti and vigne, or large aristocratic

villas such as the Villa Peretti Montalto and the Villa Ludovisi,

mentioned above. The unfortunate destruction of these two villas was

solely due to their locations, where the modern railway and

residential neighborhoods were constructed.

Some of the large villas in the suburban neighborhoods and small gardens in the city have survived. Today the Villa Borghese and the Villa Pamphilj are public parks, enjoyed by children and adults, as the lungs of the city. Parco San Gregorio on the Caelian Hill, between the Colosseum and the church of Santo Stefano Rotondo, derives from the orto of the Camaldolese monastery and preserves part of their orchard. Since the sixteenth century, the Camaldolese monks operated a charity institution for the poor and the disinherited, tending the land for the sustenance of the staff and those in need. The Parco Savello, next to Santa Sabina on the Aventine Hill, property of the Savello family in the medieval period, was owned by the Ginnasi family in Nolli’s time and subsequently by the Dominican fathers of Santa Sabina. The orange trees there were planted in remembrance of Saint Dominic, the founder of the Dominican order. Offering a moment of respite to residents and visitors alike, these gardens are a living reminder that we can retain some continuity of green Rome in contemporary urban life.